energy & environment

The (last) waltz for the internal combustion engine in Europe?

On 28 June, after just the 18 hours of deliberation, the French Presidency managed to build consensus among European Environment Ministers for a General Approach on CO2 targets for cars and vans.

Under pressure to find an agreement after the European Parliament (EP) approved its first-reading position on 8 June 2022, the Ministers also endorsed the phase-out of petrol and diesel models by 2035. Despite the usual last-minute negotiation twists, all three EU institutions now back up the most symbolic measure of the proposed Regulation.

Is this the end of the road for internal combustion engines in Europe?

A short recap on the key milestones that led to a historical decision.

2021: the Commission’s first-shot

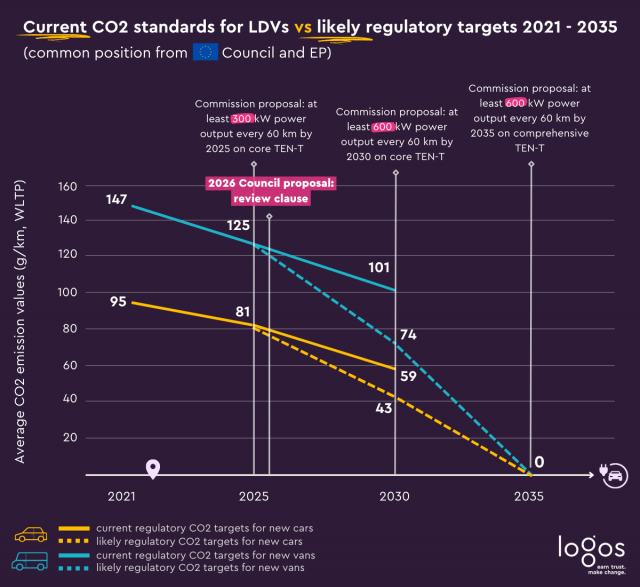

On 14 July 2021, the Commission fired the first shot in its “Fit for 55” package, requiring CO2 emissions of new cars to come down by 55% from 2030 and 100% from 2035 compared to 2021 levels.

A few years ago, this hard cut-off date would have been considered by many inconceivable. No later than 2018, Chancellor Merkel personally weighed in against a CO2 reduction of more than 30 per cent by 2030.

In 2022, nevertheless, CO2 targets were not even the most controversial part of the package, as half of the College refused to endorse the inclusion of road transport and building under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). Even The European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA)’s official position was milder and did not dismiss the proposed 2035 -100% target frontally, calling instead for post-2030 targets to be set only during a review in 2028.

However, the industry’s narrative was challenged from within. Pushed by investors, many OEMs have recently made public announcements about their electrification strategies. Even Stellantis, despite its CEO’s reluctance for a technology “chosen by politicians“, aims for 100% BEV car sales in Europe by 2030 in its Dare Forward 2030 plan. The final blow came from Ford Europe and Volvo Cars, who signed a joint appeal to back the proposed 2035 targets in May 2022.

From then on, it became hard (if not impossible) to fight back against the ban on ICE vehicles, despite German VDA’s attempts. Hence the focus in ACEA’s narrative is on an interim review clause and conditionality principle, e.g. mandatory charging infrastructure targets and other measures that the car industry deems imperative to achieve the targets.

A few years ago, this hard cut-off date would have been considered by many inconceivable. No later than 2018, Chancellor Merkel personally weighed in against a CO2 reduction of more than 30 per cent by 2030.

First battleground: the European Parliament

Nonetheless, in the EP, the outcome of the vote remained uncertain until the last minute, largely due to internal misalignment within the rapporteurs’ centrist group, Renew.

The right-wing (ID, ECR, and EPP) and left-wing (Greens, socialists, and the Left) political groups stuck to their classic tunes. The conservative parties opposed the ban on internal combustion engines. The EPP supported a new crediting system for “sustainable renewable fuels” to incentivise their use by car manufacturers. On the contrary, the Greens strongly backed the phase-out date and even called on the EU to introduce a 2027 interim target.

However, while the Rapporteur Jan Huitema (Renew, Netherlands) endorsed the Greens’ proposals, Dominique Riquet (Renew, France) – who drafted the ITRE Opinion – objected to the ban promoted by his colleague, stating that such a ban goes against the principle of technology-neutrality.

The 2027 interim target ended up being rejected during the plenary vote, shedding light once more on the pivotal role played by Renew. In the past, the two majority blocks in the EP, namely the EPP and S&D, allowed for greater predictability. Now, the ever-shifting and multi-party alliances led to much lower vote certainty. In the end, MEPs stuck to the targets initially proposed by the Commission, namely:

- -15% emissions by 2025 for both cars and vans;

- -55% emissions for cars and -50% for vans by 2030;

- -100% emissions by 2035 for both cars and vans.

Despite the ICE ban, MEPs agreed to the so-called “Ferrari amendment” by delaying the phase-out of derogations for small-volume manufacturers (less than 10 000 cars or less than 22 000 vans newly registered per year) from 2030 to 2036.

ACEA immediately reacted to the European Parliament’s adoption of the 2035 ban on internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles arguing that a long-term regulation (going beyond this decade) was premature and called instead for a periodic review “halfway”, given the “volatility and uncertainty” the industry is facing. With the EP largely backing the Commission’s proposal, all eyes turned towards the Council.

MEPs agreed to the so-called ‘Ferrari amendment’ by delaying the phase-out of derogations for small-volume manufacturers from 2030 to 2036.

The Council tango

Things did not start well with a last-minute coalition initiated by Italy together with Portugal, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, and later joined by Poland, who sought to delay the 100% reduction target by 2040. Some (e.g. Sweden and Ireland) arguing on the contrary that this was the minimum they could agree upon.

The German “traffic light” coalition then made it even worse, exposing their internal divide publicly as the FDP opposed the ban on ICE vehicles by 2035. While discussions were ongoing in the Environment Council, Finance Minister Lindner (FDP) publicly undermined his own delegation and Environment Minister Lemke (Greens), arguing that her position did not match the coalition’s agreement:

Die Äußerungen der Umweltministerin zum #VerbrennerAus sind überraschend. Sie entsprechen nicht den Verabredungen. Verbrennungsmotoren mit CO2-freien Kraftstoffen sollen als Technologie auch nach 2035 in allen Fahrzeugen möglich sein. Daran ist unsere Zustimmung gebunden. CL https://t.co/swbYHNh16y

— Christian Lindner (@c_lindner) June 28, 2022

Eventually, the French Presidency, with the Commission’s support, negotiated what some consider a delicate balancing act, some others a fool’s bargain. The final deal will allow combustion engine vehicles to remain authorised after 2035, as long as they do not emit any CO2. Matching ACEA’s demands, the Council also included a 2026 review clause requesting the Commission to assess whether the targets remain realistic or require further adjustment. To end the Presidency on a pinnacle rather than a failure, the French compromise also conceded to Italy and maintained derogations for small-volume manufacturers until the end of 2035 (instead of 2030 as proposed by the EC).

VP Timmermans had no trouble endorsing the deal as it maintained the most symbolic measure: 2035 remains the landmark date by which new LDVs must emit zero CO2 to be sold in Europe. As for the concessions made to Germany and its allies, VP Timmermans astutely stated that “the Commission will have an open mind” on e-fuels but insisted that the burden will anyway be on the industry to demonstrate their viability.

Although the ICE phase-out date is clearly the most newsworthy item, once again, it was the ETS and the Social Climate Fund that sparked a violent backlash among the Member States. To a large extent, the CO2 Regulation was nothing more than a bargaining chip as the Council sought to strike a deal on four other texts simultaneously (the ETS, the Social Climate Fund, the Effort-Sharing Regulation in non-ETS sectors, and emissions from Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry).

Eventually, the French Presidency, with the Commission’s support, negotiated what some consider a delicate balancing act, some others a fool’s bargain.

What’s next?

The European Parliament and the Council will now start the trilogues, aiming for a final agreement by the end of 2022. In theory, since the Council and Parliament’s positions are relatively close, negotiations should be smooth but will the Czech Presidency be the party-crasher?

Although CZ Prime Minister Fiala previously shared his intent to ease up the rules for car OEMs during the country’s Presidency, revisiting the hard-fought Council agreement seems highly unlikely. The Czechs will most likely try to secure as much flexibility as possible for the industry on the final deal, maintaining the 2026 revision clause and future assessment on e-fuels. On the latter, it remains to be seen how hard the Parliament will fight back against the symbolic “e-fuel clause”.

Now that the direction on CO2 targets is clear, the Commission will be able to come forward with the next batch of emission legislation targeting road transport: Euro 7/VII (regulating among other NOx emissions) and CO2 standards for heavy-duty vehicles. Delayed twice, as the Commission sought to reflect the direction the political wind was blowing around CO2 for cars and vans, both proposals have been pushed back again to the end of 2022.

Since the essential components of its CO2 targets remained untouched, the Commission is likely to consider it has a “carte blanche” to push highly ambitious targets in these two texts as well.