space

Race to space connectivity: crisis in the making, human right or strategic interest?

The last few years have seen satellite connectivity projects pop up around the world, from SpaceX’s Starlink, the UK-Indian One Web, to the EU’s Secure Connectivity Initiative and similar developments in China (GalaxySpace and others) and Canada.

These projects vary slightly: some aim only to provide fast internet connectivity to unserved or underserved areas, others have more ambitious goals of powering tomorrow’s digital solutions, but all imply sending a large number of small satellites into orbit (anywhere between 800 to 42,000 satellites).

While it remains unclear for those projects still in their infancy, such as the EU’s Secure Connectivity Initiative, most intend to have these satellites operate in the low Earth orbit, or LEO. However, as of 2019, NASA estimates that around 6,000 tonnes of debris are already located in the LEO.

This tremendous amount of space debris is cause for concern, but COVID-19 has revealed that access to the internet is becoming increasingly necessary in our daily lives. Where does the balance lie?

Since humans began exploring space, a total mass of more than 7,500 tonnes of space debris has accumulated, of which around 6,000 tonnes are located in the LEO.

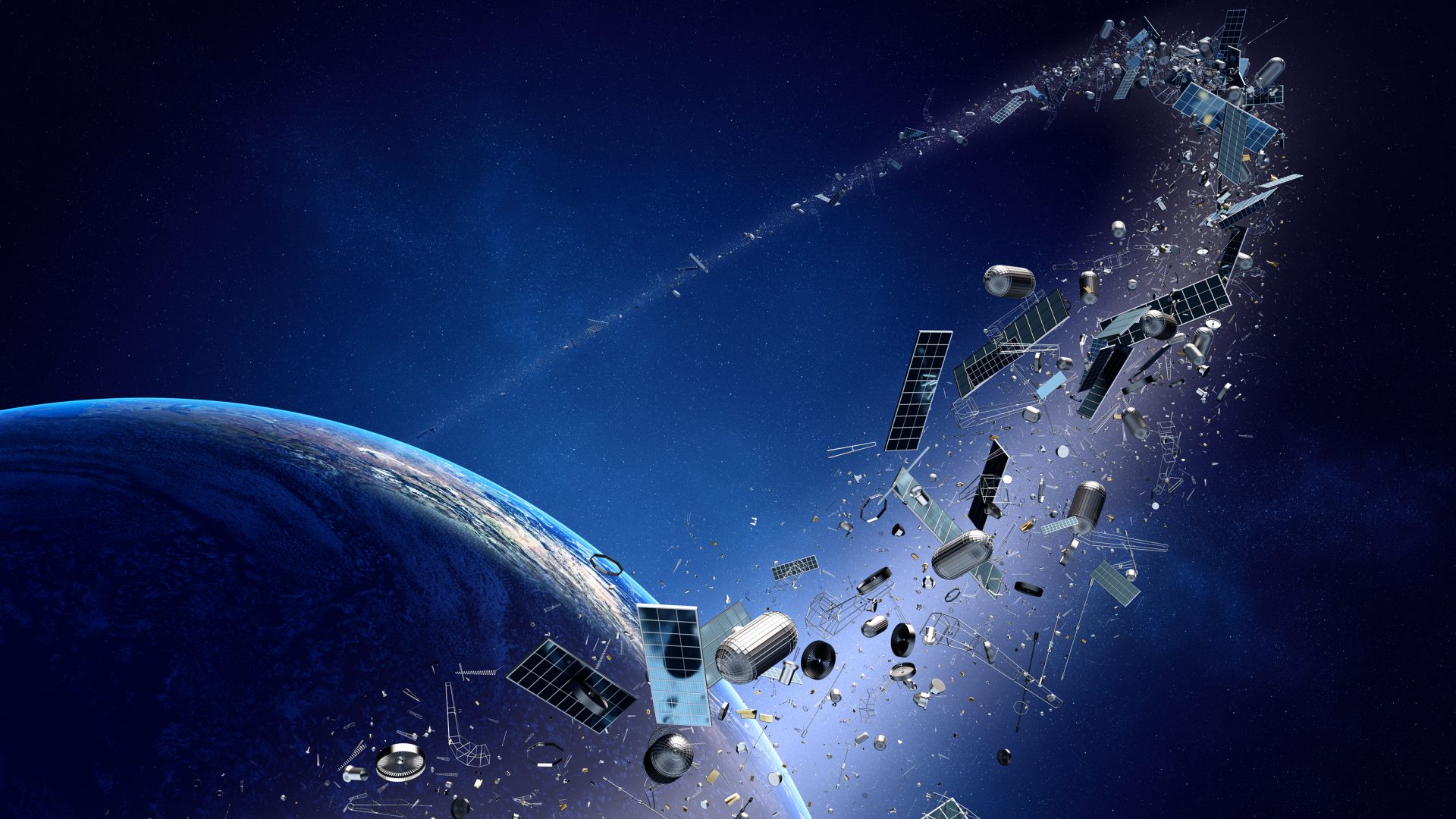

Space debris: the next big sustainability crisis

Since humans began exploring space, a total mass of more than 7,500 tonnes of space debris has accumulated, of which around 6,000 tonnes are located in the LEO. This space debris is made up of satellites that are no longer operational, parts of launchers and space crafts, as well as much smaller objects such as paint flecks. With such a large amount of space debris floating around, collision is becoming increasingly unavoidable. With each collision, more debris is generated, further threatening operational satellites and space missions, such as the ISS, which by the end of 2020 had already carried out 26 manoeuvres to avoid collisions with space debris.

During the 8th European Conference on Space Debris, Holger Krag, head of the European Space Agency’s Space Debris Office, said: “Hundreds of collision avoidance alerts are issued every week to satellite operators. Their spacecrafts then have to carry out costly collision avoidance manoeuvres, about once every two weeks in the case of ESA’s 20 satellites”.

Space debris is not only an issue in space; it is also causing growing concern “on the ground”. Increasing numbers of satellites in the LEO could compromise scientists’ ability to observe distant objects in space or cause interference for telescopes using specific radio frequencies to study deep space.

Adding thousands of internet connectivity satellites to the mix could seriously endanger the future of space infrastructure and services, as well as ground-based science. Why then are so many of these projects coming about around the world?

Overnight, access to (reliable) internet became indispensable for work, education and much more. Yet, around the world, including in Europe, many still lack internet access, particularly people in already marginalised communities.

Connectivity above sustainability: internet access as a human right

For over a year now, Covid-19 forced most of the world to go virtual at an unprecedented rate. Overnight, access to (reliable) internet became indispensable for work, education and much more. Yet, around the world, including in Europe, many still lack internet access, particularly people in already marginalised communities.

This has put in the spotlight the idea of ‘access to the internet’ as part of a new generation of human rights. In 2016, the UN adopted a non-binding regulation that recognised internet access as a human right, or rather condemned taking away access to the internet as it would constitute a violation of online freedom. Yet, as the pandemic has shown, access to the internet goes far beyond ‘online freedom’.

In a July 2020 letter published in La Repubblica, European Parliament President David Sassoli stated: “access to the internet must be recognised as a new human right”, highlighting that lack of internet access affects the right to education and knowledge, the ability to work and communicate with loved ones, access news and essential information (including on the pandemic itself), and even buy food. Lack of (reliable) access to the internet can generate inequalities and further marginalise affected populations.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, joins Sassoli in urging the world to recognise internet access as a human right. As he puts it, referring to the internet during the pandemic: “in this crisis, for those who have it, the web is not a luxury. It’s a lifeline”.

It is undeniable then that projects such as Starlink, One Web, or the EU’s Secure Connectivity Initiative, could play a vital part in ensuring that individuals and families around the world can enjoy this fundamental right.

Yet, concerns around space debris and sustainability are just as crucial. If access to the internet is recognised as a universal human right, shouldn’t this call for a universal solution, where governments around the world join efforts to ensure connectivity for all?

In the interest of safeguarding existing and future vital satellites, as well as ground-based science, the EU should think twice about the necessity of having its own dedicated infrastructure.

Sovereignty and strategic autonomy above all – a sign of the times

From space and digital, to research and the green transformation, the European Union is increasingly seeking to establish its sovereignty and reach autonomy in these strategic areas. It is not alone in this endeavour, as the United States and China have shown they are already several steps ahead in many key aspects.

While most satellite connectivity projects have commercial aims, the EU’s secure connectivity initiative aims not only to bring internet to unserved/underserved areas, but also to provide secure communication services to the EU and its Member States, strengthening European digital sovereignty and powering the digital solutions of tomorrow. As EU Commissioner Thierry Breton put it: “We cannot afford to be dependent on emerging connectivity constellations that are non-Europeans”.

However, this ambition to ensure sovereignty and strategic autonomy above all, even if that means adding another mega satellite constellation to an already overcrowded LEO (and GEO – Geosynchronous Earth Orbit) is somewhat contradictory to the EU’s ‘Green’ agenda. In the interest of safeguarding existing and future vital satellites, as well as ground-based science, the EU should think twice about the necessity of having its own dedicated infrastructure.

Rather, the EU could position itself at the forefront of the movement to recognise access to the internet as a human right, concluding strategic partnerships with existing (commercial) satellite connectivity projects, thus reinforcing its commitment to putting sustainability at the centre of its policies and establishing itself as a world leader in the protection and implementation of the next generation of digital human rights.

However, in the absence of any comprehensive international regulation on space debris and an increasing commercial and political eagerness to send thousands of small satellites into orbit, LEO might just be set to become the next great pacific garbage patch. One thing seems clear at least: in the race to space connectivity, it is to each to his own.