political analysis

‘Le Premier Tour’: Five key takeaways from the French presidential elections

Tactical voting x3

A glimpse at the results of the 1st round may lead one to believe that France’s politics is now clearly structured around three unidimensional blocks. Each gathers 20-25% of the electorate: the far-right with Marine Le Pen, President Macron’s liberal bloc in the centre and the green, anti-capitalist far-left rallied around Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

Although all other candidates peaked below 5% (except for Eric Zemmour, Le Pen’s frenemy, at 7%), this picture may reflect the polarisation of French presidential elections rather than being an accurate depiction of the power balance among political forces in France.

A look at other recent elections provides a much different analytical grid. In the 2019 European Parliament election, Mélenchon’s party ended second to last at 6,31%, a meagre 0,12% above the Socialists. In the 2020 local elections, the Greens prevailed in many significant cities while incumbents from the traditional Socialist or “Les Républicains” parties held most of their seats. Combined, these three parties now total just about 11% in the first round. So, what happened?

Simple: the fear of the inevitable binary choice during the second round. Anticipating a duel they could not suffer, voters picked the most likely candidate to qualify against the other undesirable two racing ahead in the polls rather than their personal favourite. Zemmour, Pécresse, Jadot, Hidalgo, all suffered from this ruthless logic.

Mélenchon and Macron should not overestimate the political capital this offers them. It is everything but a solid commitment to their persona, programme, or guarantee that there won’t be another “lesser evil” in the future. Even Marine Le Pen, unless she wins on 24 April, should not consider Zemmour’s threat as fenced off in anticipation of upcoming legislative elections (now commonly referred to as the “3rd round of the presidential elections”).

Anticipating a duel they could not suffer, voters picked the most likely candidate to qualify against the other undesirable two racing ahead in the polls rather than their personal favourite.

The threat of Le Pen President is for real this time

In 2017, Macron was considered a new, refreshing political figure who successfully positioned himself as neither right nor left, or rather en même temps (both at once). His positive campaign and a succession of unexpected factors (the scandal of Francois Fillon, for example) allowed him to win against the odds and all historical parties. During the usual pre-second round TV debate versus Marine Le Pen, his debate skills and preparedness (or lack thereof from his opponent) helped him secure a comfortable win.

Five years later, it’s not the same drill: he is now the incumbent President, with a track record and a series of political choices to defend (especially in response to the Yellow Vests’ movement), which many consider as clearly leaning towards the right-wing. His campaign was sluggish, partly by tactical choice, partly due to the war in Ukraine.

Despite the fact that all historic institutional candidates are calling upon their electors to either vote Macron or “to give zero votes to Le Pen”, under the front républicain (mainstream parties calling electors to support whoever stands against the far-right) will not be an easy ride. Reserves are short: some left-wing figures expressed post-election night that Macron will have to go after each left-wing voter “one by one”, stating that they have been “humiliated” during his mandate.

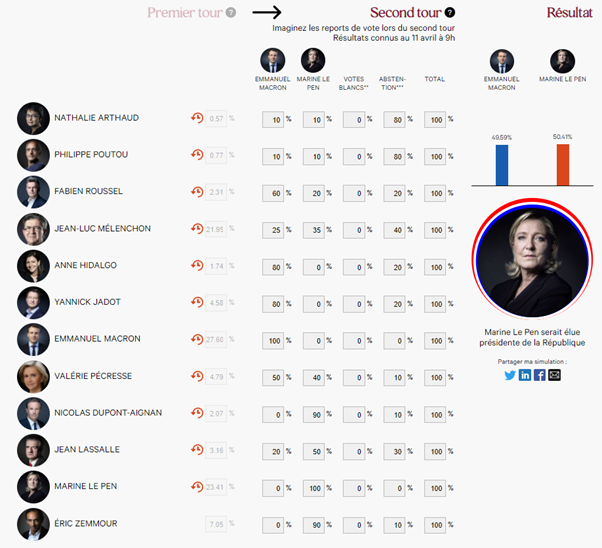

Assuming around 50-80% of voters from Pécresse, Jadot, Roussel or Hidalgo following their candidates’ words to back Macron, this only gives him about 2,3 – 3,7 million votes versus 2,6 – 2,85 million for Le Pen, just assuming 80-90% support from Zemmour and Dupont-Aignan voters. These two candidates are ideologically much closer than the formers to Macron.

You can create your prediction with this simulator.

In 2017, Macron was considered a new, refreshing political figure who successfully positioned himself as neither right nor left, or rather en même temps […]. Five years later, it’s not the same drill.

Second round X Factor: Mélenchon

The numbers show that the third man holds one of the keys to the 2nd round, even though he does not own his electorate. For what is meant to be his last campaign, the (far) left-wing figure came out clearly against Marine Le Pen during his post-results speech, unlike in 2017, where he refused to give clear voting instructions. Nonetheless, for many left-wing voters who backed Mélenchon, there is evident wear and tear of the “front républicain”. The resentment is high against Macron and his policies, perceived as dismissive of the lower-income class and destructive to what remains of the post-WWII French welfare state. Back in 2017, a viral social media quote among left-wing voters was, “a vote for Macron in 2017 is a vote for Le Pen in 2022”.

Unfortunately, Macron failed to lower the extreme parties as he pledged to. Some even accuse him of having fuelled Marine Le Pen purposely by taking over some of her narratives to secure a remake of the 2017 elections. Ironically, many perceived it as a more favourable scenario than a confrontation with a mainstream candidate.

Caught between what they regard as Scylla and Charybdis, many within the left-wing electorate, especially the working class, will abstain as they refuse to give another 5-year blank check to Macron. The temptation for many to vote for Marine Le Pen is high. She rebranded herself as a “mainstream but tough” right-wing politician during this campaign, thanks to Zemmour’s extremist, anti-muslim outbreaks that softened her image.

A realistic scenario, assuming a constant abstention level and 80% vote transfer from Jadot, Hidalgo to Macron vs 90% of Zemmour and Dupont-Aignan, with split votes from Pécresse, Roussel and Lassalle (the candidate defending rural France) would bring the balance very close. If Mélenchon’s electorate divides itself into 3 (one third abstain, one-third Macron, one third Le Pen), Macron would win by less than 2%, lower than any poll error margin. Change the parameters to split Mélenchon’s votes by 25% to Macron, 35% to Le Pen and another 40% abstaining, and Le Pen gets the win.

See our (obviously imperfect) simulation:

Caught between what they regard as Scylla and Charybdis, many within the left-wing electorate, especially the working class, will abstain as they refuse to give another 5-year blank check to Macron.

Macron’s first-round strategy paid off but fuelled the risk for the 2nd round

In the lead up to the election, as the Ukraine war burst out, Macron first tried, with some success, to capitalise on his statesman image. Unable to confront the incumbent, his opponents were also busy campaigning against one another to dominate their respective political spaces. Over time, critics linking his lack of commitment to the campaign as another sign of alleged contempt for the electorate began to see the dividends. Forced to unveil his proposals for the next mandate, he opted for a tactical move and a set of right-wing measures aimed at Pécresse’s electorate. Out of the limited number of proposals he made before the first round, the most salient ones for the public opinion were the postponement retirement age to 65 and conditioning social aides to some community service hours.

Pécresse found herself without any political space, squeezed between Macron occupying the centre-right and Le Pen/Zemmour on the far-right (although her poor performance on stage during political rallies also did not help). Confronted with the rise of Le Pen and Mélenchon in the polls, a significant number of voters opted for the safest best in the first round: Emmanuel Macron. Pécresse now finishes with less than 5% votes, the lowest score ever for the mainstream right-wing, and her party has plunged into a financial crisis as she missed the campaign reimbursement threshold.

Although successful for the 1st round, Macron’s move puts him at risk for the second one. His positioning learned much more on the right than in 2017 and fell short of appealing proposals to his left-wing. Such signals are dearly missed now as they would help make Macron’s ballot less of a rebuttal for Mélenchon’s voters. In contrast, Le Pen focused her campaign on protecting French workers’ purchasing power.

Macron finds himself in a tricky position without this groundwork: he needs to send a strong message to those who picked Mélenchon yet without appearing as reneging himself or hurting his right-wing credentials. Especially since he also needs to avoid a critical share of Pécresse’s voters shifting to Le Pen.

For Marine Le Pen, this may be a case of “now or never”, as the odds have never been more favourable to her ahead of the second round. Should she fail, she will credit her extreme-right contender, Eric Zemmour.

Now what?

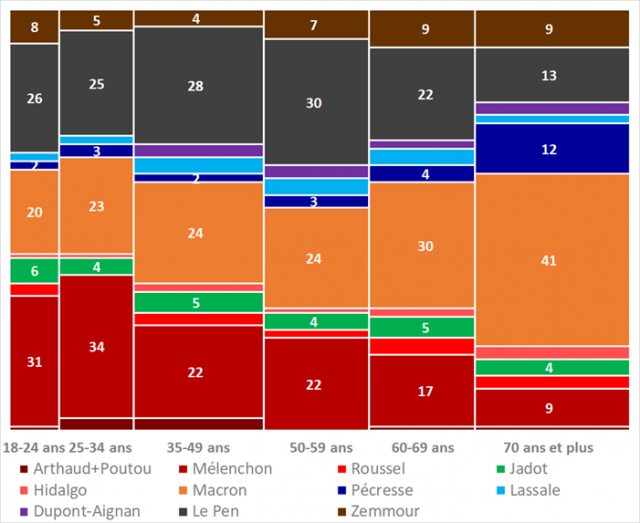

Macron has already started to appeal to younger voters (18-34) and the left who favoured Mélenchon during the first round. The trend was already perceivable in 2017 but by narrower margins. However, it is particularly noticeable; Macron was still the top candidate for the 18-24 age class until a few months ago. On 10 April, the older generations formed the backbone of Macron’s electorate, now creating resentment among the youth on social media against “spoiled baby boomers”.

Lacking the forward-looking vision and novelty that were his great strengths in 2017, it is a long way for candidate Macron to reconcile the generation gap and reconnect himself with the aspirations of the French youth. The statesmen approach has its limits. Now confronted with a high-risk second round, Macron needs to layout an inclusive project beyond his right wing in less than two weeks, especially reaching young voters and France’s so-called “diagonal void” constituted by economically struggling rural or peri-urban areas. In the non-exhaustive list of possibilities:

- break the image of the “president of the rich” with strong measures on buying power (in the context of ramping inflation) and remedying social inequality even if it means partly alienating his liberal agenda (e.g. on minimum retirement age);

- answer the youth’s aspirations by positioning the climate change agenda at the core of the next five years beyond the symbols;

- develop a comprehensive set of measures targeting French rural and peri-urban areas around medical deserts, lack of public services or public transport;

- Drop the top-down governance model and invent a new way of doing politics that offers more grasp to intermediate bodies and citizens via direct democracy (something Macron promised but failed to deliver);

For Marine Le Pen, this may be a case of “now or never”, as the odds have never been more favourable to her ahead of the second round. Should she fail, she will credit her extreme-right contender, Eric Zemmour, who claimed that “everyone knows Marine Le Pen cannot win, including herself”. His new extreme-right party might establish a lasting presence in the French political landscape, making it harder for Le Pen’s Front National to retain its leadership and secure a strong presence in the French National Assembly.

Meanwhile, La France Insoumise, Mélenchon’s party, starts a new journey, as the commitment of their charismatic leader in future campaigns is uncertain. The challenge will be the same as in the aftermath of the 2017 election: can they convert their presidential voters to form a new, enlarged basis of the party electorate? They previously failed to establish themselves as the dominant force as their voters scattered again across left-wing parties. With 50% of Mélenchon’s electorate declaring itself as tactical voters[1] (the highest rate among top candidates) according to the poll by OpinionWay for CNEWS, the answer lies in their ability (or not) to forge a balanced alliance with the Greens, the Socialists or the Communist Party. Starting with the legislative elections, it will not be an easy ride to build a joint manifesto since all these parties are fighting for survival. Ironically, La France Insoumise leader opposed such an alliance ahead of the presidential elections, stating that “you can’t make the union in the first round” before falling short of less than half-a-million votes to beat Le Pen when Fabien Roussel obtained just about 800,000.

For the second-round contenders, it is too early to bang their heads on the legislative puzzle yet, as it will largely depend on the results at 8:00 pm on 24 April. Traditionally, the elected president easily secures a majority, although it might be more complex this time.

The second round is an uphill battle for Macron this time. A winnable one still, but he will need to retrieve the political savviness that helped him win in 2017. The TV duel on 20 April will be decisive, even more so as Le Pen will have learned the lesson after her previous slip-up.